THE ENNEAGRAM

A THRIVING CULTURE RESOURCE

The Enneagram Assessment: A Thriving Culture Guide to Navigating Your Inner Landscape

Before we begin…

This guide focuses specifically on the Enneagram as a personality assessment framework, its structure, types, and practical applications. It represents one core component of the comprehensive Thriving Culture Leadership Framework, which integrates this work with cultural intelligence, trauma-informed practice, power analysis, and organizational psychology to create transformative leadership development. The full framework examines how these personality patterns intersect with systemic forces, historical trauma, and identity work, moving beyond individual insight to collective health. For information on accessing the complete Thriving Culture methodology for your organization or leadership development, please contact our team.

Now, let us explore the map itself.

Introduction: The Mirror in the Maze

Imagine you’ve been navigating a complex maze your entire life. You’ve developed brilliant strategies: perhaps you meticulously map each turn (Type One), or you follow others who seem confident (Type Six), or you charge ahead, trusting your gut to break through walls (Type Eight). These strategies work—until they don’t. You hit dead ends that feel personal. The maze itself feels designed to frustrate you.

The Enneagram is not another personality test that tells you what you’re good at. It is the gift of a mirror held up in the middle of your maze. It shows you why you chose your particular strategy in the first place. It reveals the unconscious compulsions driving your thoughts, feelings, and actions. Developed from ancient wisdom traditions and refined by modern psychology, the Enneagram posits that we are born with a full spectrum of potential, but early in life, we learn to over-rely on one way of being to secure love, safety, and significance. This hardens into a personality type—a magnificent but narrow adaptation.

For leaders, managers, healers, and change-makers, this insight is revolutionary. It transforms conflicts from “you versus me” to “my strategy versus your strategy.” It turns burnout from personal failure into a signal that your adaptation has reached its limit. This guide will walk you through the system’s architecture, the 9 profound portraits of human adaptation, and how to apply this knowledge not to label yourself or others, but to cultivate greater choice, compassion, and effectiveness in every aspect of your life and work.

Table of Contents

Part I: The History and Evolution of the Enneagram

Ancient Roots and Mystical Lineages

Gurdjieff: The Symbol Enters the Western Consciousness

Ichazo: Mapping Personality onto the Symbol

Naranjo: Psychological Depth and Clinical Validation

Academic Research and Validation: Building an Evidence Base

Synthesis: A Tool for Integration

Part II: The Architecture of a Dynamic System

The Symbol: A Diagram of Process

The Three Centers of Intelligence: Head, Heart, Body

The Triads: Revealing Deeper Patterns

The Wings: Your Neighboring Influences

The Lines of Connection: Stress and Security

The Instinctual Variants: Subtypes (The Most Overlooked Key)

Part III: The Nine Types – Portraits of Human Strategy

Type One: The Reformer

Type Two: The Helper

Type Three: The Achiever

Type Four: The Individualist

Type Five: The Investigator

Type Six: The Loyalist

Type Seven: The Enthusiast

Type Eight: The Challenger

Type Nine: The Peacemaker

Part IV: Applying the Assessment – From Insight to Integration

Step 1: Finding Your Type – A Process of Inner Observation

Step 2: Working with Your Type – Daily Practices

Step 3: Using the Enneagram in Relationships and Leadership

Step 4: Avoiding Common Pitfalls

Conclusion: The Journey Back to Wholeness

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Part I: The History and Evolution of the Enneagram: From Ancient Symbol to Modern Psychological Framework

Ancient Roots and Mystical Lineages

The Enneagram's journey from esoteric symbol to mainstream psychological tool is a rich tapestry of cross-cultural transmission, spiritual inquiry, and psychological refinement. Its modern form represents a synthesis of wisdom traditions, but its geometric symbol has far deeper historical antecedents.

The word "Enneagram" derives from the Greek ennea (nine) and grammos (something drawn or written). The symbol itself—a circle containing an inner triangle and an irregular hexagonal figure—appears in various wisdom traditions, though its precise origins remain debated. Some scholars trace proto-Enneagram symbols to Pythagorean mathematics and Neoplatonic philosophy, where geometric forms represented cosmic principles and the nature of reality. More concretely, the symbol appears in the work of the 14th-century Christian mystic Ramon Llull, who used similar diagrams in his Ars Magna to represent the dynamic relationships between divine attributes.

However, the most significant pre-modern appearance occurs within Sufi traditions, particularly the Naqshbandi order. Here, the symbol was known as the "Face of God" and served as a contemplative diagram representing the process of spiritual transformation and the interconnectedness of all existence. It was transmitted orally and secretly, a sacred geometry used to illustrate the dynamic laws governing human consciousness and cosmic order.

Gurdjieff: The Symbol Enters the Western Consciousness

The figure entered modern Western thought through the enigmatic Armenian-Greek spiritual teacher George Gurdjieff (c. 1866-1949). After extensive travels through Central Asia and the Middle East in search of esoteric knowledge, Gurdjieff introduced the Enneagram symbol to his students in Russia and later in France. For Gurdjieff, the Enneagram was not a personality typology but a universal symbol of process.

He taught that it represented the "Law of Seven" (the irregular hexad) interacting with the "Law of Three" (the triangle), governing all cosmic and human processes—from the baking of bread to the development of consciousness. Gurdjieff's Enneagram was a dynamic model of energy transformation, used to analyze movements, music (his "Movements" or sacred dances), and the stages of any complete process. His central teaching was that humans live in a state of "waking sleep," mechanically reacting to stimuli, and that conscious work—guided by understanding laws symbolized by the Enneagram—was required for awakening. He famously stated, "A man may be born, but in order to be born he must first die, and in order to die he must first awake." The Enneagram was a map for this awakening.

Ichazo: Mapping Personality onto the Symbol

The crucial leap from a cosmological symbol to a system of personality types occurred through Oscar Ichazo (b. 1931), a Bolivian-born teacher. In the 1950s and 1960s, Ichazo synthesized elements from diverse sources—including Gurdjieffian work, Kabbalah, Sufism, Ch'an Buddhism, and Platonic philosophy—into a comprehensive system called the Protoanalytic Theory.

Ichazo founded the Arica School in Chile and later moved it to the United States. He was the first to systematically associate specific psychological and spiritual themes with the nine points on the Enneagram symbol. He identified:

The Ego Fixation: A compulsive mental pattern characteristic of each point.

The Passion: A dominant emotional vice or "capital sin" (reconceptualized psychologically).

The Holy Idea: A lost essential virtue or perception of reality that, when reclaimed, liberates one from the fixation.

Ichazo taught that these nine points represented nine distinct ways the human ego crystallizes around a core illusion following a perceived separation from the Divine or essential nature. His work provided the foundational architecture of the Enneagram of Personality, framing it as a path of self-observation and return to one's essential being.

Naranjo: Psychological Depth and Clinical Validation

The system was brought to a wider, psychologically-minded audience by Dr. Claudio Naranjo (1932-2019), a Chilean psychiatrist who studied with Ichazo in Chile in the early 1970s. Naranjo, steeped in Gestalt therapy, psychodynamic theory, and his own clinical experience, became the crucial bridge between Ichazo's metaphysical system and Western psychology.

Naranjo's monumental contribution was to flesh out the behavioral, cognitive, and emotional profiles of each type through deep clinical interviews and observation. He conducted intensive residential workshops in Berkeley, California, where he used the Enneagram as a diagnostic framework, linking it to character structures from psychoanalytic tradition (like the work of Karen Horney and Freud). He emphasized the clinical usefulness of the system for understanding defense mechanisms, interpersonal patterns, and pathways to healing.

From Naranjo, the teaching passed to his students, including Helen Palmer, Don Riso, and Russ Hudson, who became the primary popularizers of the Enneagram in North America from the 1980s onward. Palmer emphasized intuitive and narrative approaches, while Riso and Hudson developed detailed models of health levels and a widely-used assessment tool (the RHETI), systematizing the framework for a mass audience.

Academic Research and Validation: Building an Evidence Base

While spiritual in origin, the Enneagram has attracted growing scholarly attention for its descriptive power and clinical utility. Research has evolved from anecdotal validation to more rigorous statistical analysis. Below are key studies that constitute the emerging evidence base.

1. Hook, J. N., Hall, T. W., Davis, D. E., Van Tongeren, D. R., & Conner, M. (2021). The Enneagram: A systematic review of the literature and directions for future research. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(4), 865-883.

This is arguably the most important modern academic review. The authors analyzed 104 published and unpublished studies on the Enneagram. Their conclusions were significant: research "generally supports the reliability and validity of the Enneagram as a measure of personality." They found evidence for its discriminant and convergent validity (it correlates with but is distinct from other personality models like the Big Five) and noted promising associations with mental health, relationship satisfaction, and spiritual outcomes. The study provided a robust, peer-reviewed affirmation of the Enneagram as a legitimate psychological construct and laid out a clear agenda for future high-quality research.

2. Newgent, R. A., Parr, P. E., Newman, I., & Higgins, K. K. (2004). The Riso-Hudson Enneagram Type Indicator: A validation study. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 37(2), 95-103.

This study provided crucial early statistical validation for a major Enneagram instrument. Using factor analysis on data from 745 participants, the researchers found support for the theoretical nine-factor structure of the Riso-Hudson Enneagram Type Indicator (RHETI). They reported acceptable internal consistency for most scales, lending scientific credence to the Enneagram as a measurable and structured model. This work helped move the Enneagram from purely descriptive territory toward psychometric respectability.

3. Sutton, A. (2012). But is it real? A review of research on the Enneagram. The Enneagram Journal, 5(1), 5-19.

Sutton's review in the first academic journal dedicated to the Enneagram provided a comprehensive, critical overview of the research landscape up to that point. He documented the Enneagram's strong face validity and its correlations with established models like the Five-Factor Model (Big Five) and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Sutton also frankly addressed methodological limitations in early studies and called for more sophisticated, large-scale research—a call that helped catalyze the next wave of scholarly work.

4. Palmer, B., & Gannon, J. (2017). The Enneagram and Psychotherapy: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry, 8(5), 00504.

This review focused specifically on clinical applications, documenting how therapists use the Enneagram to enhance their own self-awareness, understand client defense mechanisms, and tailor therapeutic interventions. It positions the Enneagram as a valuable framework within a trauma-informed and relational therapeutic context, highlighting its utility in building the therapeutic alliance and conceptualizing cases beyond pathology.

5. Matise, M. (2007). The Enneagram: An enhancement to family therapy. The Family Journal, 15(4), 367-371.

Matise demonstrated the Enneagram's systemic utility by applying it to family systems theory. The article shows how mapping family members' types can illuminate intergenerational patterns, communication breakdowns, and pathways to healing. This work is directly translatable to organizational "family systems," providing a framework for understanding team dynamics, leadership-board conflicts, and organizational culture through a typological lens that avoids blame.

6. Daniels, D. N., & Price, V. A. (2000). The Essential Enneagram: The Definitive Personality Test and Self-Discovery Guide. HarperOne. (The Scientific Basis)

While a book for general audiences, the appendix by statistician James D. Sell provides a rigorous analysis of data from over 500,000 participants who took the authors' test (the ESSENTIAL Enneagram). Sell reports strong test-retest reliability and validity coefficients, with correct self-typing rates significantly above chance. This large-N data set from a commercially available instrument offers compelling real-world evidence for the model's consistency and recognizability.

7. Edwards, C. (1991). The Enneagram: A primer for psychiatric clinicians. Journal of Psychiatric Education, 15(1), 35-41.

An early article that introduced the Enneagram to the clinical psychiatric community. Edwards argued for its usefulness in understanding patient character structure, predicting transference and countertransference dynamics, and formulating treatment plans. It represents an early effort to bridge the Enneagram from spiritual circles into mainstream clinical practice.

8. Mayer, J. D. (2004). How does personality influence the Enneagram? A theoretical model and preliminary empirical test. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 24(2), 119-148.

This study, from a respected personality researcher, explored the relationship between the Enneagram and established trait theories. Mayer found predictable correlations, such as Enneagram Type Seven with high Openness and Extraversion on the Big Five, providing construct validity by showing the Enneagram aligns with—yet offers something distinct from—major academic personality models.

Synthesis: A Tool for Integration

The history of the Enneagram reveals its unique character: it is a bridging framework. It bridges ancient wisdom and modern psychology, spiritual insight and clinical utility, self-awareness and systems thinking. Its validation lies not only in statistical coefficients but in its profound explanatory power in therapy rooms, leadership workshops, and personal transformation journeys.

The research, while still developing, consistently points toward the Enneagram's reliability as a descriptive map of human motivation and its practical value in applied settings. For the Thriving Culture leader, this evidence base allows us to engage the Enneagram with intellectual integrity—honoring its roots while applying it rigorously to the complex tasks of leading diverse, trauma-impacted organizations toward greater wholeness and impact. It stands not as a revealed dogma, but as a profoundly useful heuristic, continuously refined through both empirical inquiry and the lived experience of those who use it to navigate their inner and outer worlds.

Part II: The Architecture of a Dynamic System

The Enneagram’s power lies in its dynamic, interconnected structure. It is not a static box but a living map of human motivation.

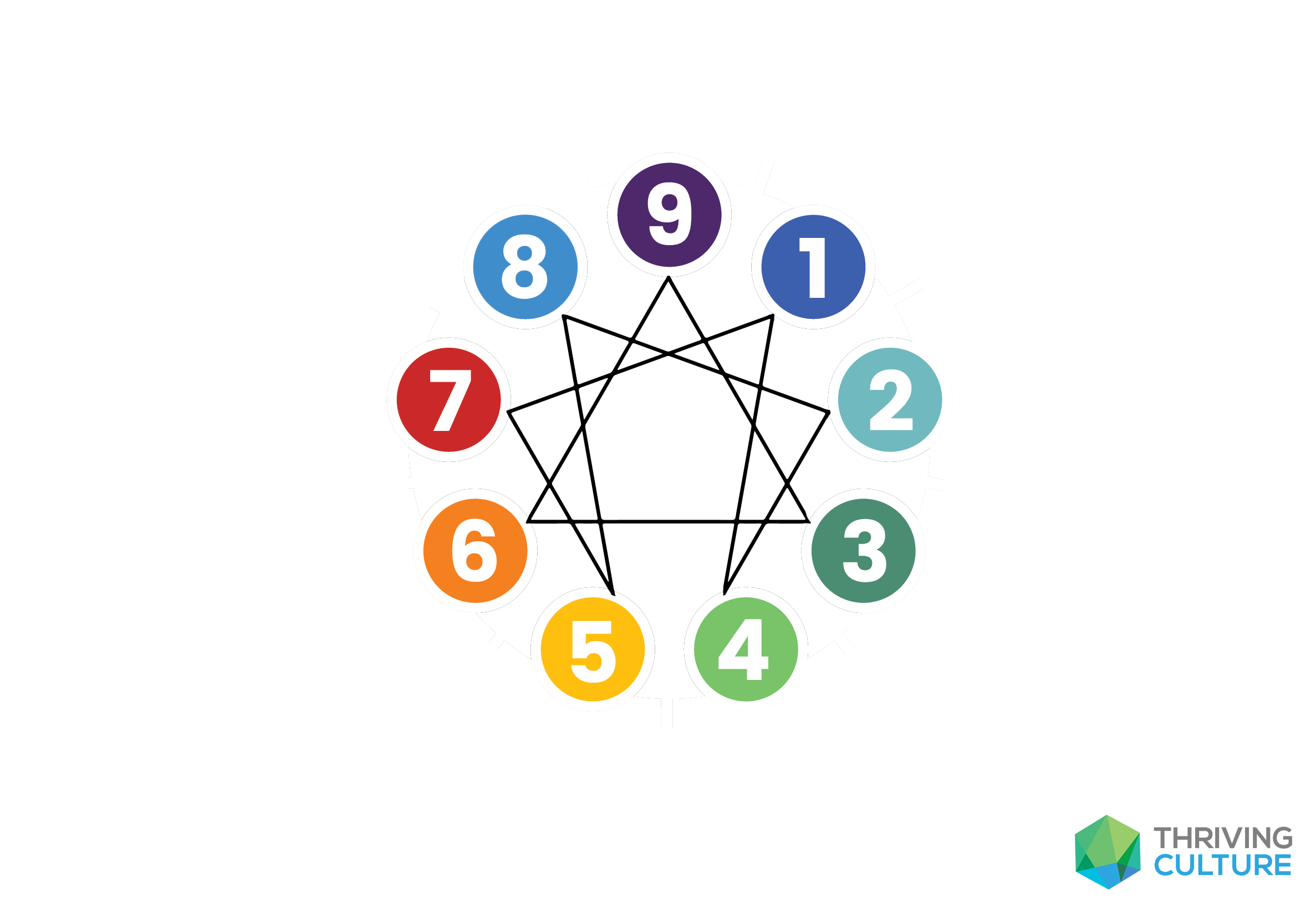

The Symbol: A Diagram of Process

The word “Enneagram” comes from the Greek ennea (nine) and grammos (a drawing). Its symbol, a circle containing a triangle (connecting points 3, 6, 9) and a six-pointed figure (connecting 1-4-2-8-5-7)—is a geometric representation of process and integration. The circle represents wholeness, the triangle symbolizes a law of three forces, and the connecting lines show pathways of movement and influence. This tells us immediately: our type is not an isolated island. We are connected to other ways of being, and we move between them under stress and growth.

The Three Centers of Intelligence: Head, Heart, Body

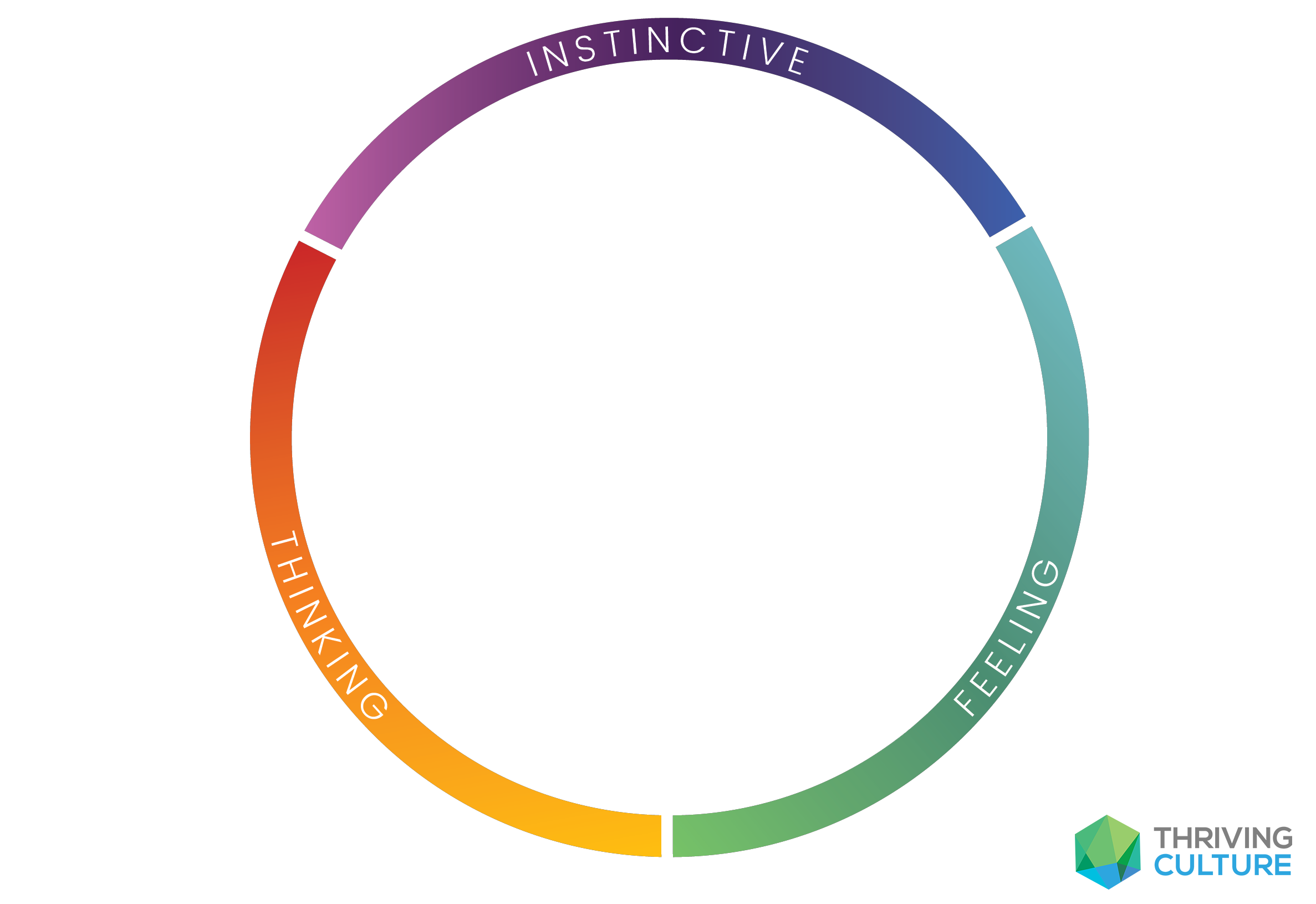

The foundation of the system is the understanding that we process reality through three core centers: the Head (Thinking), the Heart (Feeling), and the Body (Instinctive). We all use all three, but our personality type is characterized by being anchored in one, while the others become under-developed or operate in the background.

The Heart Center (Types Two, Three, Four): These types are anchored in the realm of emotions, image, and relationships. Their core attention goes to questions of identity and worth: “Who am I in the eyes of others? Am I worthy of love and attention?” Their gift is emotional intelligence and empathy. Their trap is becoming identified with a role or image they present to the world to secure validation, often losing touch with their authentic, underlying feelings.

The Head Center (Types Five, Six, Seven): These types are anchored in the realm of thinking, analysis, and future planning. Their core attention goes to questions of safety and guidance: “How do I navigate a world that feels unpredictable or overwhelming? Who can I trust?” Their gift is strategic thinking and foresight. Their trap is becoming lost in mental constructs—scenarios, plans, or information—which can disconnect them from present-moment experience and gut-level certainty.

The Body Center (Types Eight, Nine, One): These types are anchored in the realm of instinct, gut feeling, and action. Their core attention goes to questions of autonomy and integrity: “How do I maintain my boundaries, my standing, or my correctness in a world that seems to impose on me?” Their gift is a visceral sense of knowing and grounded action. Their trap is becoming identified with gut reactions—anger, aggression, or numbing—which can manifest as controlling their environment, withdrawing from conflict, or striving for an impossible perfection.

Practical Insight: Understanding centers helps diagnose team and organizational dysfunction. Is your team all heart (passionate but lacking strategy)? All head (analytical but tone-deaf)? All body (decisive but resistant to new ideas)? Health requires balancing all three intelligences.

The Triads: Revealing Deeper Patterns

Beyond centers, the Enneagram groups the types into powerful triads that reveal deeper psychological patterns.

The Harmony Triads (Hornevian Groups): How We Engage the World

The Assertive Types (Three, Seven, Eight): Move against their environment. They are energetic, self-confident, and work to shape the world to their needs.

The Compliant Types (One, Two, Six): Move toward their environment. They are highly attuned to external expectations, rules, and the needs of others.

The Withdrawn Types (Four, Five, Nine): Move away from their environment. They need space for reflection and preserve energy by creating inner boundaries.

The Object Relations Triads: Our Childhood Strategy for Love

Based on the work of psychiatrist Claudio Naranjo, this triad describes our early strategy to secure connection with caregivers.

The Attachment Types (Three, Six, Nine): Believed they had to modify themselves to be loved. They became adaptable, seeking to fit in or find their place.

The Frustration Types (One, Four, Seven): Felt that something essential was missing in their connection. They cope by seeking an ideal: perfect order, authentic identity, or the perfect experience.

The Rejection Types (Two, Five, Eight): Felt they had to reject their own needs or risk being rejected. Twos reject their needs to care for others, Fives reject emotional needs for self-sufficiency, Eights reject vulnerability for strength.

The Wings: Your Psychological Neighbors and Resource Bank

The concept of wings is what transforms the Enneagram from a rigid, nine-box system into a fluid and nuanced portrait of individuality. If your core type is your psychological home address—your fundamental structure of motivation and defense—then your wings are the neighborhoods on either side. You can visit them, draw resources from them, and are inevitably influenced by their character. No person is a "pure" type; we are all a unique blend of our core number and the energy of one or both adjacent numbers.

Understanding Wing Theory: More Than Just Influence

A wing is one of the two types adjacent to your core number on the Enneagram circle. For Type Nine, the wings are Eight and One. For Type Four, they are Three and Five. The wing is not a separate type you "are," but a modifying filter that shapes how your core type's motivation manifests in the world.

There are three primary configurations:

A Dominant Wing: One wing is significantly more developed and active, creating a clear "flavor" (e.g., a 6w5 or a 6w7).

Balanced Wings: Both wings are accessed fluidly and with relative equilibrium, though one may be more contextually active.

Minimal Wing Expression: The core type's energy is so pronounced that the wings are less distinct, though they are never entirely absent.

A Thriving Culture Insight: The development of a wing is often influenced by life experience, cultural expectations, and familial modeling. For example, a Type Three in a culture or family that highly values relational harmony may more readily develop their Two wing, while one in a context that prizes artistic individuality may lean into their Four wing. This is not random; it’s an intelligent adaptation within the larger type structure.

The Wing as Resource and Shadow

Your wings provide essential resources that your core type may lack, but they also bring potential blind spots.

The Supporting Wing: Often acts as a resource center, offering tools and perspectives that help you meet your core type's agenda. For a Type Six, the Five wing offers analytical depth and the ability to withdraw to think, while the Seven wing offers optimism and the ability to reframe threats into possibilities.

The Challenging Wing: Can represent a shadow or tension point, manifesting in ways that feel less integrated or more conflictual with the core type's self-image. A Type One with a strong Nine wing may struggle with inertia (the Nine's shadow) that frustrates their One desire for reform, while their Two wing might manifest as a prickly, repressed need for appreciation that clashes with their self-image of selfless integrity.

Detailed Wing Profiles: How They Modify the Core Type

Let's examine how wings modify two central types as examples, demonstrating the profound impact they have on leadership style and interpersonal dynamics.

Example: The Type Six – The Loyalist

The Six’s core motivation is security, seeking guidance and certainty in an uncertain world.

6w5: "The Defender/The Questioner"

Expression: This Six internalizes their anxiety, leading with a thoughtful, analytical, and prepared demeanor. They seek security through knowledge, competence, and self-sufficiency. They are the researchers, the contingency planners, the deep thinkers who want to understand systems to feel safe.

Strengths: Intellectual depth, independence of thought, calm under pressure (once they've analyzed the threat), highly expert.

Risks: Can become overly withdrawn, isolated in their analysis, and pessimistic. Their doubting mind (Six) combined with Five's detachment can lead to profound skepticism and alienation from the group they seek to secure.

Leadership Style: The strategic guardian. Leads by building robust systems and protocols. Values expertise and foresight. May need to consciously work on relational warmth and group morale.

6w7: "The Buddy/The Companion"

Expression: This Six externalizes their anxiety through engagement and activity. They seek security through alliances, community, and positive reframing. They are the team-builders, the networkers, the ones who manage fear by staying busy and connected.

Strengths: Warm, engaging, loyal, able to lighten the mood and bring people together. More optimistic and adaptable.

Risks: Can become scattered, over-committed, and avoidant of deep, quiet fears through constant activity. Their need for reassurance (Six) combined with Seven's gluttony for experience can lead to dependency on external stimulation and affirmation.

Leadership Style: The collaborative coach. Leads by building trust and team cohesion. Values morale and collective problem-solving. May need to consciously work on focused, independent decision-making and sitting with difficult, unresolved tensions.

Example: The Type 3, The Achiever

The Three’s core motivation is to be valuable and successful, avoiding failure and worthlessness.

3w2: "The Charmer/The Star"

Expression: Achievement is channeled through relational influence and being of service. This Three is highly attuned to what others value and adept at tailoring their image to be likable, helpful, and successful. They are the charismatic leaders, the persuasive fundraisers, the ones who achieve with and for others.

Strengths: Charming, empathetic, team-oriented, able to read a room and inspire collective effort. Their ambition is wrapped in warmth.

Risks: Can confuse being liked with being valuable. May struggle with boundaries, over-identify with the helper role, and repress their own needs to maintain the admired image.

Leadership Style: The inspirational ambassador. Leads by motivating teams and building key relationships. Success is measured in both metrics and morale. Shadow appears as people-pleasing and image-management at the cost of authenticity.

3w4: "The Professional/The Expert"

Expression: Achievement is channeled through unique competence, personal brand, and depth. This Three is less overtly gregarious and more focused on being the best in a specific, often niche, field. They care about being not just successful, but distinctively so. They are the innovative entrepreneurs, the artistic achievers, the thought leaders.

Strengths: Authentic, refined, driven by a desire for quality and uniqueness over pure mass appeal. More introspective and comfortable with complexity.

Risks: Can struggle with envy (the Four wing), melancholy, and isolation. Their drive for a unique image can create a sense of alienation or competitiveness that undermines teamwork. May oscillate between grandiosity and self-doubt.

Leadership Style: The visionary expert. Leads by exemplifying exceptional standards and innovative thinking. Success is measured in legacy, originality, and mastery. Shadow appears as elitism and emotional volatility.

Integration and Disintegration Through the Wings

The wings also provide clues to your type's movement. Sometimes, under stress, you may exhibit the negative aspects of your less-developed wing. In growth, you can consciously cultivate the positive aspects of either wing as a resource. For instance, a stressed 9w1 might not only become anxious (disintegration to Six) but also hyper-critical and rigid (negative One wing). A growing 9w8 could learn to access the Eight's healthy assertiveness to voice their needs, while a 9w1 could access the One's sense of personal integrity to define their own stand.

Practical Application: Working with Your Wings

Identify Your Wing: Observe which adjacent type's strategies you naturally and consistently employ to meet your core motivation. Which feels more like "home"?

Leverage Your Dominant Wing: Ask, "How does my wing help me? What resource does it provide my core type?" Intentionally use it as a strength.

Explore Your Other Wing: Consciously practice accessing the positive qualities of your less-dominant wing. This is a direct path to psychological expansion. A 2w3 could practice the One wing's focus on personal boundaries and integrity; a 2w1 could practice the Three wing's healthy self-promotion and ambition.

Watch for the Shadow: Be mindful of when your wing manifests in negative, compulsive ways—often when you are tired or stressed. This is a signal to return to your core type's growth path.

In essence, your wings are your psychosynthesis toolkit. They complete the picture of who you are, explaining the rich variation within each type and providing accessible pathways for development. To know your type without exploring your wings is to have a map with only the highways marked, missing all the local roads that give the landscape its true character.

The Lines of Connection: Stress and Security

The lines connecting the types on the symbol are pathways of movement, revealing how we change under different conditions.

The Direction of Disintegration (Stress): Under pressure, we unconsciously take on the negative qualities of another type. For example, a normally composed Type One under severe stress can become moody and irrational, mimicking an unhealthy Four.

The Direction of Integration (Growth/Security): When we are self-aware and secure, we consciously adopt the positive qualities of another type. That same Type One, in growth, can become more spontaneous and joyful, like a healthy Seven.

This dynamic model is crucial—it means we already possess all nine types within us. Our type is our home base, but we travel. Awareness of these lines allows us to catch ourselves in stress patterns and intentionally cultivate growth.

The Instinctual Variants: Subtypes

(The Most Overlooked Key)

This is where the Enneagram achieves breathtaking precision and where most casual users go astray. Within your core type, a dominant instinct profoundly colors its expression. We have three core human instincts—Self-Preservation (SP), Social (SO), and Sexual (or One-on-One, SX)—and we stack them in a hierarchy of dominant, secondary, and blind spot.

Self-Preservation (SP): Focused on personal security, comfort, health, resources, and the immediate physical environment. The SP instinct asks, “Am I safe? Do I have enough?”

Social (SO): Focused on belonging, status, role within groups, social dynamics, and collective values. The SO instinct asks, “Where do I belong? What is my role and value in this group?”

Sexual (SX) / One-on-One: Focused on intensity, intimate bonds, chemistry, fusion, and the energy exchange between individuals. The SX instinct asks, “Where is the vitality? Who or what fascinates me?”

A Social Type Four is concerned with their unique role and identity within the community. A Self-Preservation Type Four focuses on creating an aesthetically perfect home or wrestles with a sense of inner deficiency related to resources or comfort. A Sexual Type Four is drawn to intense, transformative one-on-one connections and dramatic emotional experiences.

You cannot accurately identify your type without understanding subtypes. They explain why two people of the same core type can look vastly different.

Part III: The Nine Types,

Portraits of Human Strategy

Here, we explore each type through the lens of core motivation—the deepest “why” behind the behavior. Remember, this is about underlying structure, not superficial traits.

Type One: The Reformer

Core Motivation: To be good, right, ethical, and to improve the world. To avoid flaw, corruption, and criticism.

The Adaptive Strategy: “I must be perfect and correct to be safe and worthy.” Often develops in environments where mistakes were met with judgment or love was conditional on “good” behavior.

Basic Fear: Being corrupt, evil, defective.

Basic Desire: To be good, to have integrity.

Key Traits: Principled, purposeful, self-controlled, perfectionistic. The inner “critic” is a constant companion.

At Their Best (Integrated): Wise, discerning, inspiring. Their high standards uplift everyone. They become ethically flexible and joyful.

Under Stress (Disintegrated): Become moody, irrational, and emotionally volatile (moving to unhealthy Type Four).

Growth Path: Learning that imperfection is human. Embracing “good enough.” Practicing self-compassion before offering correction to others.

Type Two: The Helper

Core Motivation: To be loved, needed, and appreciated. To avoid being unwanted or unloved.

The Adaptive Strategy: “I must earn love by anticipating and meeting the needs of others.” Adapts to environments where attention came through caregiving or where needs were seen as burdensome.

Basic Fear: Being unloved, unwanted.

Basic Desire: To feel loved.

Key Traits: Generous, demonstrative, people-pleasing, possessive. Exquisitely attuned to others’ emotions, sometimes at the expense of their own.

At Their Best (Integrated): Unconditionally loving, humble, self-aware. Their help is freely given without strings.

Under Stress (Disintegrated): Become aggressive, claiming they’re “owed” for their help, and can become controlling (moving to unhealthy Type Eight).

Growth Path: Recognizing their own needs as valid. Learning to receive. Asking “What do I feel?” before asking “What do you need?”

Type Three: The Achiever

Core Motivation: To be valuable, successful, and admired. To avoid failure, insignificance, and worthlessness.

The Adaptive Strategy: “I must become what is valued to be loved.” Often develops where affection was tied to performance or achievement.

Basic Fear: Being worthless, a failure.

Basic Desire: To feel valuable, worthwhile.

Key Traits: Adaptable, excelling, driven, image-conscious. Masters of efficiency and presenting the “ideal” self for any situation.

At Their Best (Integrated): Authentic, inspiring, a role model of true excellence. They lead from genuine substance, not just image.

Under Stress (Disintegrated): Become apathetic, defeatist, and give up on goals (moving to unhealthy Type Nine).

Growth Path: Slowing down to connect with their authentic feelings beneath the roles. Valuing being over doing. Cultivating intrinsic self-worth.

Type Four: The Individualist

Core Motivation: To be unique, authentic, and deeply understood. To avoid being ordinary, flawed, or lacking a significant identity.

The Adaptive Strategy: “Something essential is missing in me. I must find my unique, authentic self to be worthy of love.” Often arises from feeling fundamentally different or that a key emotional connection was missing.

Basic Fear: Having no identity or personal significance.

Basic Desire: To find themselves and their significance.

Key Traits: Expressive, dramatic, self-absorbed, temperamental. Drawn to beauty, depth, and the melancholic. They fear being mundane.

At Their Best (Integrated): Profoundly creative, self-renewing, empathetic. They transform suffering into art and deep human connection.

Under Stress (Disintegrated): Become overly critical, detail-obsessed, and rigid (moving to unhealthy Type One).

Growth Path: Shifting focus from what’s missing to what’s present. Taking constructive action in the real world. Seeing their common humanity, not just their unique difference.

Type Five: The Investigator

Core Motivation: To be competent, knowledgeable, and self-sufficient. To avoid helplessness, incompetence, and intrusion.

The Adaptive Strategy: “The world is intrusive and demanding. I must withdraw to build my own competence and resources.” Often develops where the world felt overwhelming or where emotional needs felt unmet, leading to retreat into the safe world of the mind.

Basic Fear: Being useless, helpless, or incapable.

Basic Desire: To be capable and competent.

Key Traits: Perceptive, innovative, secretive, isolated. They are conceptualizers who seek to understand the world by thinking about it.

At Their Best (Integrated): Visionary pioneers, able to synthesize complex ideas and share their insights with the world. Deeply engaged and connected.

Under Stress (Disintegrated): Become scattered, hyperactive, and superficial (moving to unhealthy Type Seven).

Growth Path: Engaging with the world, sharing knowledge, and trusting they have “enough” inner resources to handle connection. Embodying their insights.

Type Six: The Loyalist

Core Motivation: To be secure, supported, and certain. To avoid danger, ambiguity, and being without guidance or support.

The Adaptive Strategy: “The world is unpredictable and threatening. I must find safety in authority, systems, or community.” A quintessential adaptation to unreliable or unsafe early environments, leading to hyper-vigilance.

Basic Fear: Being without support or guidance.

Basic Desire: To have security and support.

Key Traits: Committed, security-oriented, engaging, suspicious. They excel at anticipating problems and are either phobic (seeking safety) or counterphobic (confronting fear head-on).

At Their Best (Integrated): Internally stable, courageously loyal, and deeply trusting of themselves and others. They build resilient communities.

Under Stress (Disintegrated): Become arrogant, dismissive of others, and overly self-reliant (moving to unhealthy Type Three).

Growth Path: Developing an inner sense of authority and trust. Distinguishing between real threat and imagined anxiety. Taking courageous action despite fear.

Type Seven: The Enthusiast

Core Motivation: To be happy, fulfilled, and free. To avoid pain, deprivation, and being trapped in negative emotion.

The Adaptive Strategy: “Pain and limitation are unbearable. I must keep my options open and focus on the positive to feel free and fulfilled.” Often develops where early pain was overwhelming or where joy was truncated, leading to a focus on future possibilities and positive reframing.

Basic Fear: Being deprived, trapped in pain.

Basic Desire: To be satisfied and content.

Key Traits: Spontaneous, versatile, acquisitive, scattered. They are the eternal optimists and possibility generators, addicted to new experiences.

At Their Best (Integrated): Focused, appreciative, joyful. They experience deep satisfaction in the present moment and follow through on their inspirations.

Under Stress (Disintegrated): Become rigid, pessimistic, and overly critical (moving to unhealthy Type One).

Growth Path: Learning to stay present with all experiences, including pain and limitation. Committing deeply. Discovering that focus leads to greater fulfillment than endless options.

Type Eight: The Challenger

Core Motivation: To be strong, in control, and protect themselves and the vulnerable. To avoid weakness, vulnerability, and being controlled or harmed.

The Adaptive Strategy: “The world is a jungle where only the strong survive. I must be powerful and in control to be safe and to protect what’s mine.” Often develops where vulnerability was punished or where they had to become their own protector early on.

Basic Fear: Being harmed, controlled, or vulnerable.

Basic Desire: To protect themselves and determine their own course in life.

Key Traits: Self-confident, decisive, willful, confrontational. They seek truth and justice, dislike pretense, and respect strength.

At Their Best (Integrated): Magnanimous, protective, using their strength to empower others. They become vulnerable, open-hearted leaders.

Under Stress (Disintegrated): Become secretive, isolated, and paranoid (moving to unhealthy Type Five).

Growth Path: Allowing vulnerability and softness. Recognizing that true strength includes receptivity. Using power to uplift, not just to dominate.

Type Nine: The Peacemaker

Core Motivation: To be at peace, in harmony, and to avoid conflict and loss of connection. To avoid conflict, tension, and asserting needs that might disrupt harmony.

The Adaptive Strategy: “My own needs and presence are disruptive. I must merge with others and the environment to maintain peace and connection.” Often develops where their presence was overlooked or where conflict was terrifying, teaching them to self-erase.

Basic Fear: Loss, separation, conflict.

Basic Desire: To have inner stability and peace of mind.

Key Traits: Accepting, trusting, stable, complacent. They are natural mediators who see all sides and seek the common ground.

At Their Best (Integrated): Indomitable, action-oriented, and fully present. They mediate conflicts with great skill and assert their own agenda with clarity.

Under Stress (Disintegrated): Become anxious, frantic, and scattered (moving to unhealthy Type Six).

Growth Path: Recognizing their own needs and anger as valid and important. Rightfully occupying space. Learning that authentic peace sometimes requires necessary conflict.

Part IV: Applying the Assessment – From Insight to Integration

Knowing your type is just the beginning. The real work is integration—using this awareness to expand your choices and relax the compulsive grip of your personality structure.

Step 1: Finding Your Type, A Process of Inner Observation

Forget online quizzes that give you a result in five minutes. Typing yourself is a contemplative process. Read the core motivations and fears. Ask yourself:

What is my fundamental, daily preoccupation?

What negative emotion (anger, shame, fear) is most familiar to me?

What do I do when I feel insecure?

Look at the stress and growth arrows. Do you recognize yourself in those movements?

Most importantly: Study the subtypes. Your dominant instinct will often make the type “click.”

Step 2: Working with Your Type – Daily Practices

Each type has a specific path of awareness.

Ones: Notice when your inner critic speaks. Practice saying “This is good enough.” Allow yourself a small, deliberate imperfection.

Twos: Pause before offering help. Ask yourself “What do I need right now?” Practice receiving compliments or help without deflection.

Threes: Schedule “non-productive” time. Check in with your feelings by name. Ask “Who am I when no one is watching?”

Fours: When feeling envious or deficient, list what you actually have. Take concrete action on a creative idea instead of just dwelling on it.

Fives: Engage before you feel fully prepared. Share a piece of knowledge without being asked. Notice sensations in your body.

Sixes: When anxious, distinguish between a possibility and a probability. Make a small decision without consulting others. Acknowledge your own courage.

Sevens: Sit with a minor discomfort (a tedious task, a difficult emotion) without escaping into planning. Complete one project before starting another.

Eights: Practice vulnerability by sharing a doubt or fear with someone you trust. Pause before reacting. Ask “Is my intensity needed here?”

Nines: Voice a preference or opinion in a low-stakes situation. Notice when you’re “numbing out” and gently bring your attention back. Get physically active to connect with your energy.

Step 3: Using the Enneagram in Relationships and Leadership

Communication: Understand your type’s communication style and the style of others. A direct Eight needs to soften for a sensitive Four. A detailed One needs to summarize for a big-picture Seven.

Conflict Resolution: See conflict as a clash of strategies, not character. A Six’s questioning isn’t disloyalty; it’s their security process. A Three’s impatience isn’t personal; it’s their drive for efficiency.

Team Building: Build teams with type diversity. Ensure all three centers are represented. Use the language of the Enneagram to appreciate different contributions: “We need your Five analysis, your Two heart, and your Eight push to make this happen.”

Leadership Development: Identify your leadership shadow. Are you a visionary Three who neglects details? A stabilizing Nine who avoids hard decisions? Use your growth arrow to develop missing capacities.

Step 4: Avoiding Common Pitfalls

Don’t use it as a label. You are not “a Four.” You have a Four personality structure. You are more than your type.

Don’t type other people. You can suspect, but only they can truly know. Offer it as a mirror, not a box.

Don’t excuse bad behavior. “I’m just an angry Eight” is an abdication of responsibility. The Enneagram explains the why, it doesn’t excuse the impact.

Don’t stop at the number. Dive into wings, arrows, and especially subtypes for a full picture.

The Journey Back to Wholeness

The Enneagram assessment is ultimately a map of a journey home—back to the wholeness that existed before we needed a personality to protect us. It shows us the magnificent, intricate cage we built for our own safety and hands us the key.

This map reveals that our greatest weaknesses are distortions of our greatest strengths. The One’s critical eye can become wise discernment. The Two’s need to be needed can become unconditional love. The Seven’s escapism can become profound appreciation for the present moment.

For the leader, this work is not narcissistic self-absorption. It is the foundation of effective, compassionate, and sustainable impact. When you understand your own automatic patterns, you can make conscious choices. When you understand the patterns of others, you can bridge differences, delegate wisely, and create environments where people feel seen for their core motivations, not just their output.

Take this guide as a starting point. Observe yourself with curiosity, not judgment. Explore the connections on the symbol. Sit with the subtypes. Let the system reveal itself to you over time. The goal is not to achieve a “perfect” personality, but to become increasingly free from personality’s compulsive grip, so you can meet each moment, each person, and each challenge with freshness, choice, and your full human capacity.

The maze is still there. But now, you have a map, a mirror, and the growing awareness that you are not lost—you are simply on a journey, and every turn holds the potential for deeper understanding.